Emersons Green school visit

“We’re trying to create ripples of change, socially. It’s the same experience for everyone, as much as possible.” Belinda Shaw and Navin Kikabhai visited Emersons Green Primary School near Bristol and found a bustling school with inclusion at its heart.

Emersons Green Primary School in South Gloucestershire was purpose built in 2000 to include disabled young people, and perhaps this is the main factor in the development of its inclusive approach. It seems significant that because no disability-designated, separate learning areas were set up at the school when it opened, no disabled pupils are required to go to them today.

Although originally designed to accommodate physically and visually impaired students, it is evident that a broader range of impairment groups are now attending. Built for around 210 children but now with 270 attending, there is plenty of natural light and there are window blinds, contrasting colours, Braille signs and acoustic panels to mute noise for students who are neurodiverse (autistic) or have a hearing impairment. There are 53 children on the SEN/EHC register of whom 20 have Statements/EHC plans, and 12 are Resource Base pupils.

Inclusion is seen as a civil and human rights issue at Emersons Green; the school tries to embed an inclusive ethos through everyday relationships and by example as well as through assemblies and other organised activities. School outings and residential visits are carefully researched to ensure everyone can take part. The school’s British Values statement includes the following: “The pupils know and understand that it is expected and imperative that respect is shown to everyone, whatever differences we may have, and to everything however big or small.”

We visited the school for some hours during the middle of the day. We joined the children at work and play, and spoke with staff and pupils. We were welcomed by the school receptionist who introduced us to Head Teacher Karl Hemmings. He had previously been a teacher at the school, left for a while and then returned in 2016 to become Head. Karl showed us round the school during the student session. The school is easy to get around because it is on one level, doors are invariably open, and hoists, power chairs and other impairment related equipment are readily available. Facilities are available for physiotherapy and bathrooms are accessible.

Karl shared his frustrations with reduced SEN funding, having to cut teaching assistance hours, and having to argue with the local authority about the need for lunch break supervisors, currently 27 in total. As we were observing one of the classes, Karl explained the buddy system which operates in the school, and how friendships are as easily made through personal interest in a football team as in anything else. As Karl pointed out, “Well we do have a City/Rovers thing going on in this school,” and commented:

“What we find is that pupils are buddies because they’re their friends. They don’t see them as disabled because that’s all they’ve ever known in their class, what they’ve only known, disabled or not.”

Cohorts of children had been and were learning and growing up together. During this teaching session we were introduced to a Blind student who was practicing his Braille skills on a Braille typewriter. As we talked to him it was clear that this student was pleased with the progress he was making. Another student stopped us in the corridor and began signing in Makaton to us, asking how many children and siblings we had.

This was a busy school with multiple organised learning activities simultaneously taking place in classrooms, students being assisted with TAs, buddies assisting students, and students using assistive devices. School space is used flexibly, including for occasional therapy or one-to-one teaching outside the classrooms. The so-called Resource Base in the school is not an actual place or unit but refers to funding arrangements associated with the teaching/learning support of the students (Braille, signing, readers, wheelchairs, physio-equipment, assistive technology, etc.). In a sense the Resource Base is everywhere.

As our conversations delved deeper Karl talked about the frustrations of the students once they were to leave Emersons Green. There was a sense of unfairness about the students’ experiences of progression and Karl had this to say about their determination to be part of mainstream education:

“There is no secondary school out there that provides the model we provide, that’s no disrespect to them, it just doesn’t exist. … So, a high proportion of them just go to a special school … I want them to be not angry that’s not the right word but I want this young lady, and this young lady, and that young man to say ‘I deserve the same as everyone else because what my school has taught me is that I should expect that’, and they should have a voice … true pupil voice. I do feel that at the systemic level, at the local authority level, it never really comes across.”

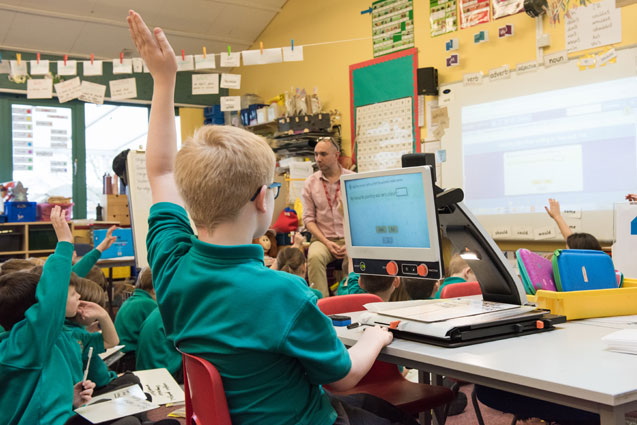

Moving on to another class, we were introduced to Matt who was working with a Year 2 class, in which there was a team of teaching assistants (TAs). It is not unusual to see three or more adults in a classroom at Emersons Green including two TAs – one might be assigned to support generally in the class while another gives more focused attention to a pupil. One of the students was using a magnifier which enabled him to access visual materials and comments on the class board without feeling excluded from spontaneous learning opportunities. For this learner this piece of equipment was “life-changing”.

Matt shared his experience of having worked at the school for sixteen years and commented on how the school was built for inclusion. He made a point of mentioning the use of technology and assistive devices in supporting the diverse range of students within the classroom, and said:

“What we don’t want is anything holding him back, and this bit of kit makes learning easier, and that they can access the curriculum. … From the very beginning the philosophy has always been about inclusion, it is about children working together… and that the children are in the classroom as much as possible. Some instances they are not but most of the time they are in here.”

It is now almost lunchtime and we meet a student having a one-to-one with a teacher specialising in Braille. This student had previously been working on his maths, English and touch-typing, and was looking forward to leaving early due to his brother’s birthday. Learning Braille is hard work and they made a point of saying that he does lots of fun things at the weekend and doesn’t take his Brailler home, although he does have a smart Brailler.

We finished conversations and made our way to the school playground, where Karl remarked:

“We’re trying to create ripples of change, socially. … It’s the same experience for everyone, as much as possible.”

The school playground was a buzz of activity. One pupil, Alice, who had recently started at the school, recalled that there were no disabled students in her previous school, and said:

“When I came here it was a very unique school. It’s really good … we always help everybody no matter if they have a disability. We treat everyone the same.”

Sadly, Alice’s comment reflects the wider reality that inclusive education is still a long way from becoming the norm everywhere and the struggle to realise the human right to inclusion for every child and young person is still very much ongoing.

For me (Belinda) the playground was the main area where the school’s inclusive ethos came alive in a personal way. Young people’s movement inside the school building itself is not overly restricted or ordered and this was also the case outside in the playground. Young people freely engaged – or not – in energetic games and other active recreation as they wished. Despite the energy, the playground felt calm and pupils used the space with awareness, avoiding getting in each other’s way. Walking slowly, as I do, I felt a great deal safer in the playground than when negotiating a main London railway station for the journey to the school. It was reassuring to find a wooden chair and other seats in the playground where pupils (or myself) could rest or take time out. The high-backed chair was appropriately engraved and dedicated to the founding head teacher of Emersons Green, Mrs Jan Isaac, and her pivotal contribution to inclusion at the school.

For me (Belinda) the playground was the main area where the school’s inclusive ethos came alive in a personal way. Young people’s movement inside the school building itself is not overly restricted or ordered and this was also the case outside in the playground. Young people freely engaged – or not – in energetic games and other active recreation as they wished. Despite the energy, the playground felt calm and pupils used the space with awareness, avoiding getting in each other’s way. Walking slowly, as I do, I felt a great deal safer in the playground than when negotiating a main London railway station for the journey to the school. It was reassuring to find a wooden chair and other seats in the playground where pupils (or myself) could rest or take time out. The high-backed chair was appropriately engraved and dedicated to the founding head teacher of Emersons Green, Mrs Jan Isaac, and her pivotal contribution to inclusion at the school.

The general atmosphere at Emersons Green is of busy organised informality. We saw a community at ease with itself – friendly and yet purposeful, focused whilst appearing chaotic in its day-to-day happenings. Challenged, engaged, respectful, confident and aware were other words which came to mind as we observed pupils at their lessons. Importantly this learning was being achieved without segregating any pupil. Flexible approaches to the curriculum, buddy systems, teaching, and pupil groupings within classrooms, as well as appropriate assistive technology and devices enabled pupils to learn together.

At Emersons Green support is based on access and participation – not separation – and on a can-do attitude that prioritises changing and developing practice as necessary and making individual adaptations and accommodations in order to find ways to include all. As Karl confidently stated: “Anybody can do it”, and added “We want to make learning work for everybody”.

Belinda Shaw and Navin Kikabhai

![Allfie [logo]](https://www.allfie.org.uk/wp-content/themes/allfie-base-theme/assets/img/allfie-logo-original.svg)